The strange economics of paying per word fragment

Every LLM interaction is metered in tokens - fragments of words that map directly to GPU cycles and electricity bills. A look at what tokens actually are and why they cost what they do.

When you use ChatGPT or Claude or Gemini, you're not paying for words. You're paying for tokens - small numerical fragments that bear only a passing resemblance to the language you typed. Understanding what tokens are, why they exist and why they carry a price tag explains more about the economics of AI than any earnings call.

What a token actually is

A language model doesn't read text. It reads numbers. Before your prompt reaches the model, it passes through a tokeniser - an algorithm that chops your text into pieces and maps each piece to an integer. Those integers are the model's vocabulary. Everything it knows, everything it generates, exists as sequences of these numbers.

The question is where to split.

You could split on every character. That gives you a tiny vocabulary - just a few hundred symbols - but forces the model to learn meaning from individual letters. The word "today" is five characters, five tokens, five separate things the model has to process and stitch together. That's computationally expensive and makes it harder for the model to learn useful patterns.

You could split on whole words. That's intuitive but creates a different problem. English alone has hundreds of thousands of words. Add in every conjugation, every compound, every proper noun, every misspelling - the vocabulary explodes. Transformer XL used word-level tokenisation and ended up with a vocabulary of 267,735. Each entry needs its own row in an embedding matrix, which eats memory proportional to vocabulary size times the model's internal dimensions. At the scale of modern LLMs, that's untenable.

The solution is subword tokenisation - a middle ground that keeps common words whole but breaks rare words into familiar fragments. The word "tokenisation" might become "token" + "isation". The model knows both pieces. It can handle the compound without needing a dedicated vocabulary entry for every possible suffix.

How subwords get chosen

The dominant algorithm is Byte-Pair Encoding, or BPE. The idea, borrowed from data compression research in the 1990s, is simple: start with individual characters, then iteratively merge the most frequent adjacent pairs.

Take a training corpus. Count every pair of adjacent symbols. The pair that appears most often gets merged into a new symbol and added to the vocabulary. Repeat. After tens of thousands of merges, you end up with a vocabulary where common words are single tokens, common prefixes and suffixes are single tokens, and rare sequences get split into smaller known pieces.

GPT-2's tokeniser ran 50,000 merges on top of a 256-byte base vocabulary, landing at 50,257 tokens total. GPT-4 uses a newer scheme called cl100k_base with roughly 100,000 tokens. Anthropic's Claude models use their own variant. Google's models lean on SentencePiece, which treats the raw byte stream as input - no assumptions about spaces or word boundaries - and applies either BPE or unigram tokenisation on top.

The differences matter more than you'd expect.

The language tax

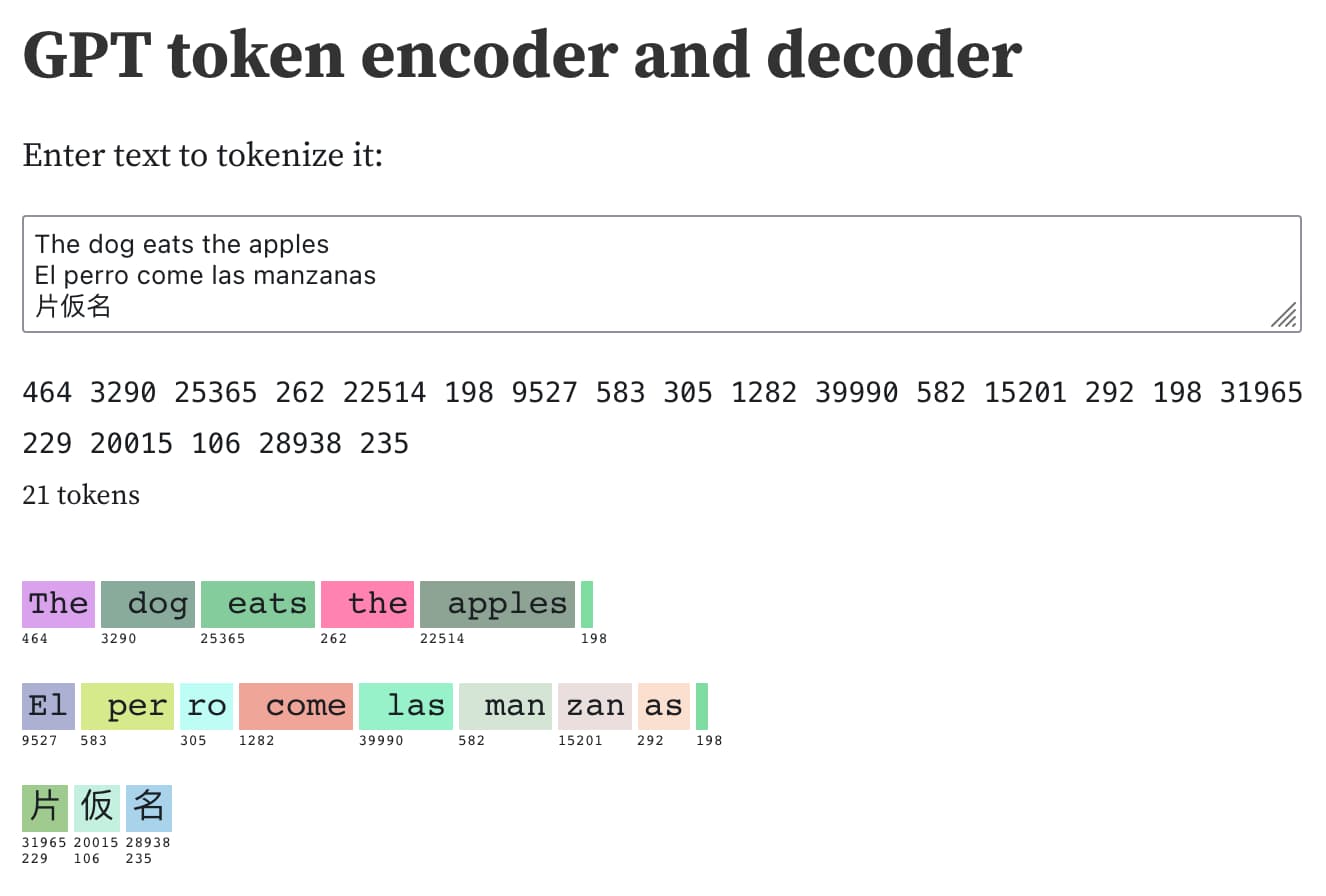

Simon Willison demonstrated something revealing with GPT's tokeniser. The English sentence "The dog eats the apples" encodes as 5 tokens. The same sentence in Spanish - "El perro come las manzanas" - takes 8. Three Japanese characters consume 6 tokens, two each.

This happens because tokenisers are trained on data that skews heavily toward English. Common English words get single-token representations. Spanish words that don't appear frequently enough in the training corpus get split. Japanese characters, which weren't part of the byte-level base vocabulary's most common merge patterns, often encode as multiple tokens each.

The practical consequence is that non-English text is structurally more expensive to process. A French speaker sends a prompt that, in English, would cost 500 tokens. The same meaning in French might cost 650 or 700. The model does the same amount of computational work per token regardless of language - so the French speaker is paying more for the same question. Not because the model charges extra, but because the tokeniser needs more tokens to represent the same information.

Capitalisation matters too. "The" with a capital T is token 464 in GPT-2's vocabulary. " the" with a leading space and lowercase is token 262. They're different tokens, processed differently, because the tokeniser treats them as distinct sequences. This is why prompt engineering sometimes produces surprising results from small formatting changes - you're not just changing words, you're changing which tokens reach the model.

Why each token costs compute

Once text has been converted to tokens, the actual work begins. Each token passes through the model's layers - typically dozens or hundreds of transformer blocks, each containing attention mechanisms and feed-forward networks. For a model with 175 billion parameters, each token triggers tens of billions of floating-point multiplications.

But the cost isn't symmetric. Reading your input and generating output are fundamentally different operations.

Input tokens can be processed in parallel. The model takes your entire prompt, feeds all tokens through the transformer stack simultaneously and builds up an internal representation of the context. GPU hardware is excellent at this kind of batched matrix multiplication. Thousands of tokens can flow through in roughly the same time as a few hundred.

Output tokens are sequential. To generate the next word, the model has to run a full forward pass through every layer, sample a token, then feed that token back as input for the next step. Each output token depends on the one before it. There's no shortcut. The model can't parallelise the generation of the 50th output token until the 49th exists.

This is why every provider charges more for output than input. OpenAI's GPT-5.2 pricing spells it out: $1.75 per million input tokens, $14 per million output tokens. That 8x ratio isn't arbitrary. It reflects the computational reality that generating text is fundamentally harder than reading it.

The machinery behind the price

Every forward pass through a model happens on a GPU - or more typically, a cluster of GPUs. These aren't the graphics cards in a gaming PC. They're data centre accelerators like Nvidia's H100 or Google's TPU v5, costing tens of thousands of pounds each and drawing hundreds of watts of power.

SemiAnalysis estimated in early 2023 that running ChatGPT cost OpenAI roughly $694,444 per day. That figure assumed about 28,936 A100 GPUs, 13 million daily active users and an average of 15 responses per user. The inference cost alone exceeded the model's entire training cost on a weekly basis.

Those numbers have shifted since. Hardware has improved. Inference optimisation techniques - quantisation, speculative decoding, attention caching - have driven costs down substantially. But the underlying structure remains. Every token your prompt consumes, every token the model generates, burns a measurable amount of electricity through a measurable number of floating-point operations on hardware with a measurable depreciation schedule.

The price you see on a pricing page isn't plucked from thin air. It's the amortised cost of silicon, power, cooling, networking and staff, divided by the number of tokens that silicon can process per second, plus margin.

Why cached tokens are cheaper

Most providers now offer a significant discount on cached input tokens. OpenAI charges $0.175 per million cached tokens for GPT-5.2, compared to $1.75 for fresh input. Google offers similar reductions across the Gemini lineup.

The reason is technical. When a model processes input tokens, it computes key-value pairs in each attention layer - essentially a compressed representation of "what this token means in context." These KV pairs are what the model actually references when generating output. If you send the same system prompt or conversation prefix repeatedly - which is exactly what happens in most applications - the provider can cache those KV pairs from the first request and skip the recomputation on subsequent ones.

The tokens still exist. They still occupy context. But the expensive matrix multiplications have already been done. What you're paying for is storage and retrieval rather than computation - which is an order of magnitude cheaper.

This is also why providers have started offering "context caching" as an explicit feature. If you're building an application that sends the same 10,000-token system prompt with every request, caching that prefix means you're paying full price once and a fraction thereafter. The economics change meaningfully at scale.

The pricing landscape right now

As of February 2026, the market has stratified into tiers that map roughly to model capability.

At the frontier, OpenAI's GPT-5.2 sits at $1.75 input / $14 output per million tokens. Their GPT-5.2 Pro - the most precise model - commands $21 input and $168 output. Google's Gemini 3 Pro charges $2 input and $12 output. These are the models you reach for when accuracy matters more than cost.

The mid-range is where most production applications live. GPT-5 mini at $0.25 / $2.00 and Gemini 2.5 Flash at $0.30 / $2.50 offer strong performance at a fraction of the frontier cost. They're the workhorses - good enough for most tasks, cheap enough to run at volume.

At the bottom end, models like GPT-4.1 nano ($0.10 / $0.40) and Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite ($0.10 / $0.40) approach near-trivial cost per query. A 500-token prompt generating a 200-token response on these models costs fractions of a penny - less than the electricity to display the answer on your screen.

The trend is unmistakable. Prices have dropped by roughly an order of magnitude each year since GPT-3.5 launched. The cheapest models today outperform the flagship models of two years ago at 1% of the cost.

What "thinking" tokens add to the bill

Reasoning models - OpenAI's o-series, Google's models with "thinking budgets" - introduce a complication. These models generate internal reasoning tokens before producing their visible response. The model might think through 2,000 tokens of chain-of-thought to produce a 200-token answer.

You pay for all of them. The thinking tokens count as output tokens at output token rates. This makes reasoning models substantially more expensive per visible word of output than their non-reasoning counterparts, even when the per-token price looks similar.

Google's Gemini pricing pages note output pricing as "including thinking tokens." OpenAI's reasoning models have historically charged at higher rates to account for the additional generation. The tradeoff is better answers on hard problems at the cost of higher and less predictable token consumption.

What this means for builders

If you're developing against these APIs, token economics shape everything. The length of your system prompt, the verbosity of your output format, whether you use JSON or natural language, how aggressively you cache context - these are engineering decisions with direct cost implications.

A chatbot that summarises documents might process 50,000 input tokens per query. At GPT-5.2 rates, that's about 9 pence per query in input costs alone. Multiply by a few thousand users and it adds up fast. The same application on Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite costs under a penny per query. The quality difference exists. Whether it matters depends entirely on the use case.

The most expensive mistake is sending tokens you don't need - verbose system prompts that repeat on every request without caching, asking the model to "think step by step" when a direct answer would suffice, or requesting structured output in a format that inflates token count. Every unnecessary token is a tiny tax that compounds at scale.

A unit of work, not a unit of meaning

Tokens aren't words. They aren't syllables. They aren't characters. They're the unit of work for a transformer model - the smallest piece the model can attend to, reason about and generate. The fact that "hello" is one token and "🤗" is three isn't a bug. It's a direct consequence of how the tokeniser was trained and what text it saw most often.

The pricing follows the work. Input tokens are cheap because GPUs handle parallel processing efficiently. Output tokens are expensive because generation is sequential. Cached tokens are cheapest because the hard computation has already been done. Thinking tokens are expensive because they're output tokens the user never sees.

Once you understand that chain - text to tokens, tokens to matrix multiplications, multiplications to GPU cycles, cycles to electricity bills, electricity to your invoice - the pricing stops being opaque. It's just physics, priced by the millisecond.

Newsletter

One email a week. Security research, engineering deep-dives and AI security insights - written for practitioners. No noise.